Published in Span Magazine, November-December 2006

Every Wednesday, Monica Jain and a few of her friends gather for a discussion session. For a few minutes, their talk revolves around social and family events, their 50-hour workweeks, their career plans. Then they move to the subject of their meeting: what they can do to improve educational access for

While the conversation is commendable in itself, what makes it remarkable is the fact that that Monica and her fellow Philadelphians do not live anywhere near India, many are not Indian and most have rarely, if ever, visited India. Most are neither well-settled professionals nor employees of an NGO. They are primarily university students attending academically rigorous American universities.

The success of this non-hierarchical, decentralized, volunteer-run and zero-overhead charity has not gone unnoticed. In 2004, Charity Navigator, an independent charity evaluator with a database of more than 3,000 organizations, ranked Asha for Education as the top charity operating on less than $2 million a year in the field of international relief and development.

For volunteers like Ravi Kandikonda, a memory chip designer in

Like Kandikonda, many volunteers of Asha’s American chapters get involved while in university. In fact, more than half of the chapters are student-run. Jain, a senior at the

Indeed, the absence of organizational red tape, coupled with Asha’s non-hierarchical structure has enabled a diversity of project types and an extensive geographical outreach within

Seed funding from Asha has often proven critical for the success of unique educational programs that may have been overlooked by mainstream funding agencies. “For our Government School Adoption Program, funding from Asha helped in providing additional teachers to the schools, which was a critical need. Though the schools had an enrollment of 250 students, they only had four teachers appointed by the government,” said Ram Krishnamurthy, coordinator of the program to strengthen government schools in Karnataka.

The ease of joining Asha is part of its appeal. Volunteers can join a chapter close to them, or if none exists, they can start one after a period of affiliation with an established chapter. The prerequisite for being a volunteer is a desire to do something for underprivileged children in India by raising funds for NGOs in India that are working to improve their plight. A chapter is free to decide what projects to fund, as long as the programs are secular and have an education component. The volunteers in each chapter democratically select a proposal to support in each funding cycle, and these must be reviewed through the main Asha data base—monitored by volunteers—before funds can be disbursed.

Volunteers in Asha’s chapters outside

“What attracts me to Asha is that, due to its decentralized structure, there is 100 percent transparency of funding, 100 percent efficiency as all the money is spent in India, and total oversight over projects because of the mandatory auditing requirements,” says James Minter, fundraising coordinator for the Asha chapter in Washington, D.C.

Though raising funds for education-related projects in

“I had to risk losing my job to volunteer, and my family is against the unpaid work and use of personal resources,” he says. “The most rewarding part of my work has been visiting project sites and seeing the faces of children light up. Volunteering doesn’t seem like work to me, but is something that springs out of my soul.”

****************

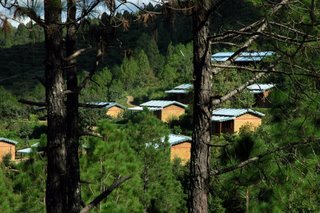

The beautiful photos are courtesy Asha Zurich.

About the photos:

projects' contribution for the development of India and to present the information to Switzerland graphically and artistically.

The three photos were taken during classes at Akshardeep, which is an alternative school program initated by the NGO Swadhar in June 1998. This project is specially meant for children of sex workers and migrant labor in the age group of 6-12. They run 10 NFE (Non Formal

Education) schools in Pune Municipal Corporation (PMC) area and 10 in Pune Chinchwad Municipal Corporation (PCMC) area. Asha Zurich is funding the running of the 10 classes.